Travel sketching is about observing and documenting. So, consider it a bonus if your sketch turns out as art. Don't worry about whether or not you will be making a good drawing. Rather, think of sketching as an experience. When you take the time to sketch you will be in a place long enough to feel the ebb and flow of people, to see the change in light, and to get the experience of local folks approaching you in their native language. You also get to sit and look at something long enough to really see it.

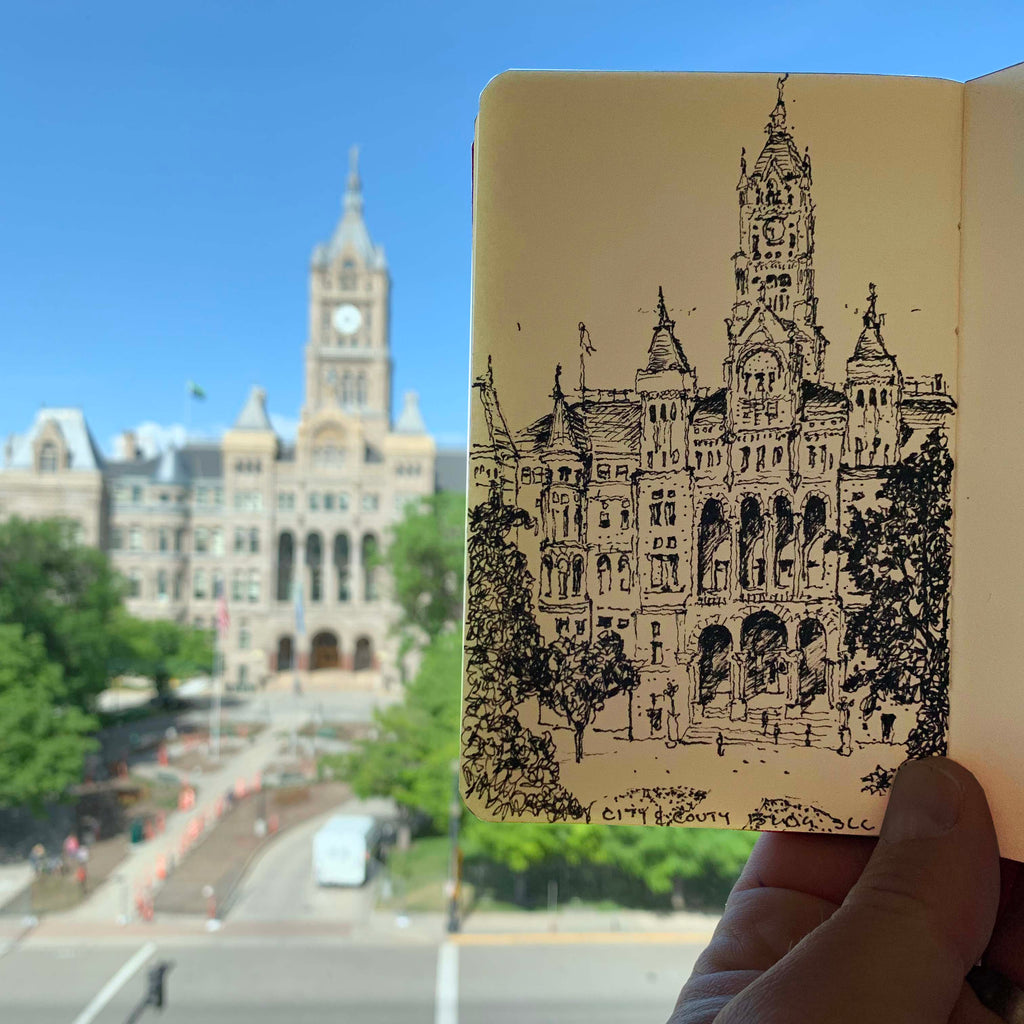

This blog post is a travel sketch lesson and case study I did as a tourist in my own hometown - step by step instructions of my sketch process for a building I’ve been meaning to sketch for years, the Salt Lake City and County Building.

Step One: Grab yourself a sketchbook and a thin felt tipped pen. It is tempting to buy more than this, but don’t – keep it simple. Make sure it has a hard cover is to protect your work. I recommend an inexpensive sketchbook to keep it from being intimidating (and too precious). I also recommend starting with a pen (not a pencil) so you can’t erase (I've seen many beginning sketchers spend more time erasing than drawing).

I’ve used many, sizes and types of sketchbooks, but my recommendation is a small book that fits in the breast pocket of a blazer. My travel sketchbook pictured below is from a company called Global Art Handbook. It has a handy little pocket in the back cover for paper relics, a convenient bookmark ribbon, and a elastic strap to help keep it closed.

Step Two: Find something you want to look at for a while. Chose something simple, but interesting. If it is too easy you will get bored and feel like quitting before you finish. For me, choosing a subject always takes time. Sometimes I’ll spend hours walking around a new city looking for a good vantage point. Maps don’t show “sketching vantage points” so you may wander into some interesting places.

What makes a good vantage point? Most importantly, it will offer a handsome arrangement of elements that you think will look good together. Or perhaps a good vantage point will allow you to study something new through your drawing. On my sketch journey yesterday, I spent about an hour looking for a compelling vantage point of the City and County Building. I was seeking a view where the trees didn’t block my view, or where the building wasn’t completely in shadow. I checked many spots: I was turned down when I asked if I could use The Green Pig bar patio at 8:15 in the morning. I wandered over to the courthouse, and into a few alleys. Then I decided to go to the east side of City Hall to check for vantage points from the Salt Lake City Public Library. I checked the Library's emergency stairs – they were alarmed. I checked the Library Plaza - not quite right. Now here is the best part: I went up a service ramp to see if I could get a better view and a friendly gentleman (the Library Director) saw that I was looking around. He offered to let me use the boardroom on the upper floor of the Library, and escorted me up the staff elevator. The vantage point came with a huge window, a table, a chair, and a fairly treeless view of my subject! Thank you, Peter!

Step Three: Now that you found a subject and a vantage point; consider where your body and hands will be for your sketch. Although I (seriously) lucked out with a chair and table directly facing my subject, it is important for you to balance your vantage point with where you place your body. Make sure your body is lined up with what you are sketching. Specifically your shoulders and face should be pointing directly towards your subject (otherwise your drawing will tend to distort, and your neck will get sore). Also consider how you will keep your arms and hands comfortable. It is tough to stand in the middle of a road or lean on a lamppost, but sometimes it is necessary. Now think about where the sun may be shining in an hour (and whether or not you want to be sitting in it – and if there will be enough light to finish your sketch). The image below illustrates how I'm sitting on a low wall facing directly at my subject so that I don't need to turn my head or body when I look up from my drawing.

Step Four: Spend some time studying your subject. For me the subject is usually an old building (I have a thing for domes, spires, full arches, deep windows, and flying buttresses). Take a few minutes deciding which parts of the composition you want to include, and which parts you want to exclude (yes it’s okay to leave things out). Now imagine a rectangle around the subject (oriented with your sketchbook page) that represents the boundary of your drawing. Or, hold your hands out in front of you to make the rectangle. The best approach is to arrange your thumb and first finger on each hand to make an “L”. Hold the first finger upward on one hand and downward on the other hand to simulate crop marks. Which way looks better, tall, or wide? Take your time, it is worth it. Next look at your sketchbook page and try to imagine the cropped arrangement overlaying your paper. Now, use your fingers like calipers to study the large ratios of the subject. Will the composition still fit on the page? Is there any white space left on the paper? Is there something else you need to leave out, or add? Does your composition need to get smaller to fit on the page? Re-adjust your rectangle and composition if necessary. This is where my heart starts racing, and I’m eager to put pen to paper, but it’s worth planning out your drawing before you start.

Step Five: Find a few major landmarks on the perimeter of your composition (the peak of a rooftop, the corner of an outer wall, the bottom of some stairs, etc). Translate a few of these landmarks onto your page with very light dots. Does your composition still fit on the page? If not, make some adjustments to the composition, or to the arrangement of dots. Now find a few more internal landmarks (perimeter of rose window, major rows of columns, flying buttress connections, etc.) and make a few more dots, or small lines indicating how these things might all fit on your page. The dots may get confusing, so take your time to plan out how your drawing will fit. If you need to abandon a dot or two, don’t worry; they will easily fade into the finished drawing. Once you’ve arranged your dots, you are about halfway finished with your sketch; surprising, right! The image below shows a few dots I jotted down after studying City Hall with my finger calipers. The small diagonal dash is where I planned to center the plaza.

Step Six: Now it’s time to commit (since you are working in pen). And, if you’re like me, your hand will be shaking slightly at this point (a bit from coffee, and mostly from adrenaline). Start with the larger shapes of the composition and pick a corner, or an edge that you want to draw; then observe which way the edge slopes within your imagined rectangle or your hand held crop marks. Is the slope horizontal (like looking out to sea)? Vertical (like a flagpole)? Sloping upward and inward (like looking down the at the floor of a hallway)? Make a mental note of the slope that you observe on your subject, and the approximate length (see my separate blog about Perspective Basics).

Now draw a line within your framework of dots to illustrate the edge of the object you are observing. Once you have a few of these edges committed, you may want to adjust your composition again. After you have a few larger shapes laid out, you will be fairly committed to your composition, but there is still flexibility with your drawing. Even if it appears that some of your composition may fall off the page, keep going.

Step Seven: Before you get too far, observe where things on your subject are dark, and where they are light. The best way to do this is to squint your eyes so you can only see your subject as a fuzzy blob. The light and dark areas will be exaggerated. Use this information as you add detail. If an area is dark, use heavier lines or some shading, or simply more detail. If an area is light, use some broken lines, and sparse detail. Below, I’ve started illustrating that the roof areas are darker, and the deep fenestration is in shade.

Step Eight: Remember that sketching is NOT about "knowing how to draw.” Rather, your assignment is to draw what you see (and you’ll be surprised by how much more you will start seeing when you start sketching). Yes, draw that funny, weird shaped little knob thing, and that oddly sloping roof (even it isn’t sloping the way you thought) and the shape of that shadow which has no geometrical name. It will also help if you give parts of your subject unusual names so you aren’t adding any pre-conceived form: i.e. I’m drawing that “mcheditty”, and here is that little “ugghme”, let’s not forget that “grheeetid” etc.

Note that in my progress image below that my sketch grew to about 25% larger than I had planned (you can tell because the diagonal dash I mentioned before – for the plaza – is now part of the tower base). At this point, I committed to leave out some of the pieces of my subject, but I decide to keep going.

Step Nine: When you get close to feeling finished, add a little more detail to emphasize lightness and darkness (remembering that on white paper, you are adding darkness and leaving lightness). Add information where you need it but don’t touch areas that look good (it’s easy to clutter up something that is subtle). This is a delicate part of the process and will become more intuitive with practice.

For my sketch of the Salt Lake City and County Building, I knew that adding trees was inevitable (which is typical). And adding trees can be intimidating since they have such odd shapes. Consider adding your trees at the end so you have flexibility resolving the main subject. And, when you start adding trees or bushes; remember to draw what you see, and use the leaves to add graphic contrast (dark against light objects, and light against dark objects). When I squinted at my composition to study the trees, they were dark so I used a dark, tight, circular shade pattern bunched up where there was shade, and more sparsely where light was coming through the trees. Once you’ve added trees, don’t forget to jot down the location, the date, and add your signature.

Here are a few other pointers to keep in mind about travel sketching:

If you are right handed, draw on the left page in your book so you can rest your right hand on the right page (reverse this if you are a lefty). With practice you can use both sides of the book, but use this technique at first for extra control.

Mistakes are okay, and may give your drawing the character that makes it look interesting. In fact, avoid calling them mistakes. Rather, think of them as surprises that you get to work with. Even if you have several surprises, try to finish your drawing. It will be tempting to tear pages out, cross out your work, or criticize a sketch too quickly. Just stick with your sketch, and work towards completing it. In the example below, there is a ghost of a tapered tower I started with, but now integrated into the finished sketch. Somehow the components got out of proportion so I needed to enlarge the left tower significantly to make the drawing work. It’s still too short, but I’m glad I finished my sketch.

You can sketch quickly or slowly and each technique will result in a different feel. Both speeds are okay. If you have an hour or more for your sketch use the whole page, if you only have a few minutes limit your sketch to the size of a postage stamp. Experiment with various speeds, and sizes. The quick thumbnail sketches below were done when I didn’t have the time to do four separate sketchbook pages. Thumbnail sketches are also a great way to study larger compositions, and overall contrast studies as well.

After you’ve given the fine pen a test drive, try out some different media: ink nib, pencils, watercolor, markers etc. Most importantly, consider whether or not the media will bleed through your notebook. It is fine if they do, just avoid soiling a prior sketch on the other side. The sketchbook page below has pencil sketches, quick pen sketches, and some bleed through from a wet sketch on the opposite side of the page. I think the variety adds interest to this entry. I never signed or dated this sketch. The arched space is from the St Genevieve Library in Paris. It took me far longer to negotiate getting a library card than it did to do this sketch.

Remember that the sketch you are working on is the only one like it in the whole world, so if it doesn’t turn out the way you expect – it’s okay! It is supposed to be different. Besides, how would you know what your drawing is supposed to look like? It didn’t already exist. If you wanted a predictable drawing you could have purchased a postcard from the souvenir shop. Look how crooked the sketch below ended up, I still like it though.

It generally takes me several sketches to get one that I’m really happy with. The trick is getting your hand relaxed and using your eyes more than your hand. Consider your hand secondary. If your dominate hand is not listening to your eyes, try using your other hand. It will feel out of control, but that’s the point. Don’t over think it. Trust your hand to follow what your eye is seeing. To make this sketch do what my eye said, I needed to bend the ceiling, and the floor.

Try giving your camera a rest. One of the best things that ever happened to me is when my camera broke as I arrived in Asia for a 90 day trip. My only option for documentation was to sketch, and it just kept getting more enjoyable. If you get clever about how to use a sketchbook for travel, it can actually be more useful than a camera. For example, the sketch below of the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela was done from several different sources: Part of the cathedral was covered in scaffolding when I arrived so a photograph would have only shown the building clad in construction fencing. I wanted to understand what the building actually looked like so I laid out the sketch, and added the information from the parts that weren’t covered, then added information shown on super graphics on the scaffolding, and I also added some information from a brochure I grabbed in the nave.

Lastly, show yourself respect by refraining from removing sketches out of your sketchbook. Each sketch is a record of that moment, and of the things you were studying. Keep them. Protect them. Make more of them. If you feel embarrassed about your sketches then keep your sketchbook private, but keep working in it.

For More:

See my related blog called Perspective Basics - How to Give your Travel Sketch More Depth

Purchase a sketching crop tool

More information about Eric Jacoby Design